As part of a new feature, Accents is proud to spotlight the Bulgarian-language poets of The Season of Delicate Hunger. Our first is Kristin Dimitrova.

Kristin Dimitrova was born on May 19th, 1963 in Sofia. She is the author of 10 books of poetry, most recently The Garden of Expectations and the Opposite Door (2012), as well as a novel, two short story collections and a set of four travelogues. Kristin is also a co-scriptwriter of the feature film The Goat (2009). She has received five national awards for poetry, three for fiction and one for the translation of a selection of poems by English poet John Donne. Her poems, short stories and essays have been translated into 24 languages and published in 26 countries. She lives and works in Sofia.

What would you like for the American readers to know about Bulgarian poetry?

The concept of “Bulgarian literature”, I am afraid, is almost as general – and therefore vague – as the concept of the “American reading public”. This makes the question a bit difficult.

I’d like American readers to know that Bulgarian poetry exists. This might sound like a somewhat minimalist wish, but it is actually a big one, touching an optic blind spot that is rarely talked about. Writers, when they feel in the limelight of media attention, or are just drunk, tend to feel overgenerous and speak about the all-transcending power of literature – crossing boundaries, permeating forbidden territories, reaching people no matter where they are. If one writes in a language spoken by 7 million people, one cannot hold for long the illusion that this works both ways.

As for present-day Bulgarian poetry in particular, I am not sure it can be described adequately in national terms; at least, this is how it looks from the inside. Poetry, being an individual and therefore a very dynamic art – unlike folk music – depends more on personal voice than on tradition. Bulgarian tradition, with all its exceptions, used to be mostly patriotic verse in the 19th c., modernism in the first half of the 20th c., socialist realism in the second half, a host of choices and styles since the 90s: actually not too far from the tradition of any other nation with a similar historical fate.

An anthology, however, is not a study in ethnography, although it could be that as well. It is the possibility of communication and this is how I see it.

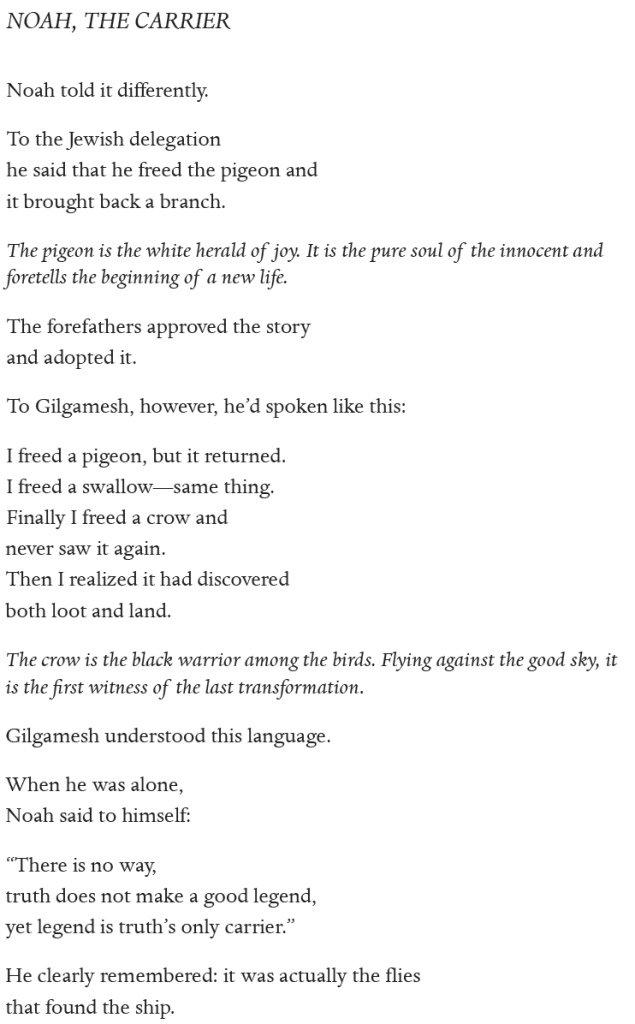

by Kristin Dimitrova.

Translated from Bulgarian by Katerina Stoykova-Klemer.

What would you like for the American readers to know about you personally?

I am the author of eleven books of poetry, one of them published in Ireland (A Visit to the Clockmaker, 2005), one in the UK (My Life in Squares, 2010) and one – The Cardplayer’s Morning – in the Czech Republic (Ráno hráče karet, 2013), two collections of short stories, Love and Death under the Crooked Pear Trees (2004), and The Secret Way of the Ink (2010) and a novel, Sabazius, translated into Russian (2012) and into Romanian (2013). There is more to this but it already sounds too detailed.

I was born and live in Sofia, I teach at the University of Sofia, I worked for a newspaper several years ago, I live with my husband who is a professor in English literature, and we have two children who are no children anymore, both of them copywriters. And we all take care of an odd-eyed cat which is deaf and dumb, dumb in the literal sense of the word, but with a very strong feeling of self-worth.

I have been to the US three times and I have some very good friends there. My impression is that America itself is much better than the “American dream”: it is full of real people.

Is there an American poet who has influenced you or has made a an impression on you? How do you interact with American poetry?

Is there an American poet who has influenced you or has made a an impression on you? How do you interact with American poetry?

Edgar Allan Poe, Sylvia Plath, Mark Strand, Forrest Gander, Stanley Kunitz, Anne Sexton, e.e. cummings, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, Emily Dickinson, Ezra Pound, T. S, Eliot, W. H. Auden – this is a disheveled list, it is so easy to forget about someone and then regret it. But some omissions are intentional. I have never really come to like the beat poets. I can appreciate the scope and power of Ginsberg’s verse, but no matter what he writes about I cannot shake off the feeling that he is too politically minded. I prefer poets who search for meaning rather than those who think they have found it and go around preaching it.

What forms of cultural exchange between Bulgaria and the U.S. would you find interesting, practical and helpful?

They are so few and far between that anything will do.

What do you wish for the anthology and its readers?

Dear reader, I wish you happy hours with this book and if the hours are not so happy, please, find another book and keep on reading. Literature is bigger than each one of us. However, knowing Katerina Klemer who made it all happen, I have my hopes.

You can read more of Kristin Dimitrova’s poetry in The Season of Delicate Hunger: Anthology of Contemporary Bulgarian Poetry, available now.

Patty Paine is the author of Feral (

Patty Paine is the author of Feral (