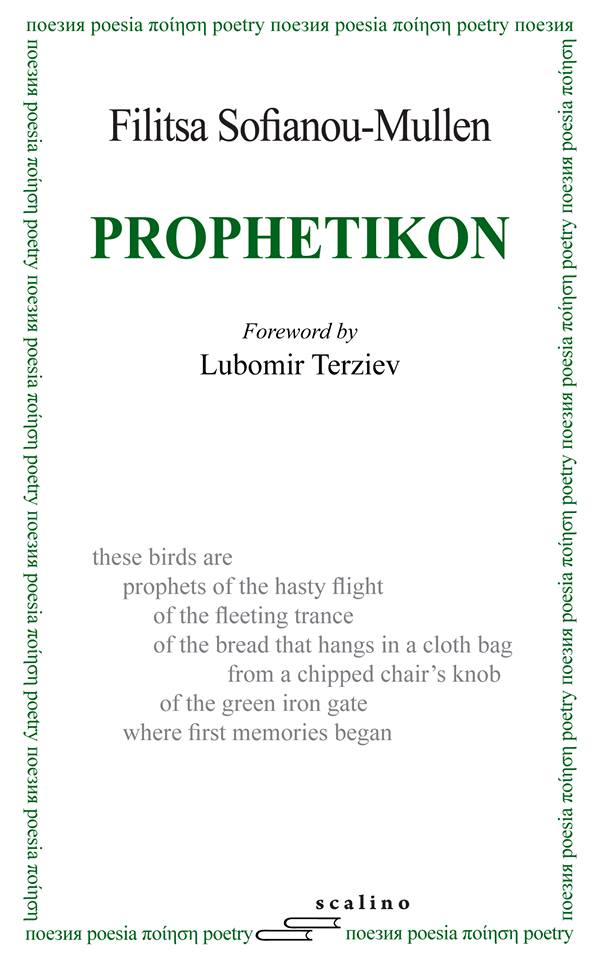

Prophetikon. Filitsa Sofianou-Mullen. Scalino, 2014. 80 pp.

No one else cares about your dreams. Or, so we’re told. More often than not, dreams are relegated (along with children and pets) to a category of things people supposedly only care about when they’re the people having them. Though, perhaps such a statement deserves more of our skepticism. Literature, and poetry in particular, is full of examples which prove writers can make their dreams compelling: from modern classics like John Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs to contemporary collections like Sarah Arvio’s Night Thoughts. Add to that list Prophetikon, the latest collection from Filitsa Sofianou-Mullen.

No one else cares about your dreams. Or, so we’re told. More often than not, dreams are relegated (along with children and pets) to a category of things people supposedly only care about when they’re the people having them. Though, perhaps such a statement deserves more of our skepticism. Literature, and poetry in particular, is full of examples which prove writers can make their dreams compelling: from modern classics like John Berryman’s 77 Dream Songs to contemporary collections like Sarah Arvio’s Night Thoughts. Add to that list Prophetikon, the latest collection from Filitsa Sofianou-Mullen.

While only some of the wonderful poems in Prophetikon are explicitly linked to dreaming, each resembles a dream in its focus and motion. Like dreams, these poems focus on images (often surreal) which hit on a visceral level. Images like travelers “riding centenarian turtles” in the poem, “III. (Immigrants),” or a woodpecker usurping a cuckoo’s nest to lay an egg in “IV. (Prophetikon I).” Though small and direct, these images seem to contain multitudes, like the lingering snapshot of a dream you might carry throughout your day, suspecting it contains revelation. Consider a poem like, “II. (Economy):”

When pennies and cents and kronas

will bubble up from the

Fontana di Trevi

they will march around to Piazza Navona

down the Spanish steps

up the Capitoline hill—

they want to return the dream

back to the pocket that kept it

secret, unspoken

less futile and cheap

than when it dipped

with a metal clink

into Roman waters.

It will be an odd parade

dangerous

this harbinger of silence

and decay.

Here, a single image—coins from the Trevi Fountain rising up to reunite with their owners—comprises the entirety of the poem. But the image, with its surrealism and complexity—in other words, with its dreamlike qualities—produces a lifespan for itself that sustains the entirety of the poem, and resonates long after.

These poems also move in a progression that recalls dreaming. Often, initiating images give way to flights of association, which are ultimately elaborated by sharp returns to reality. This can be seen in a poem like “IX. (The foundation),” in which the speaker seems to enter into a state of daydream:

In the old quarry

the ash-white dog

sniffs his own trails

overlapping

on gray-blue stones.

There were people here once

men naked from the waist up

white kercheifs tied

with four knots

on top of sweaty curls

silver with dust

women would come

quietly on the balls of their bare feet

with earth brown coffee

still in the cesve

—copper black from the coal fires of eons—

there had to be forty bubbles on the foam.

The unfinished steps go up and turn

higher and higher

a boulder marks the end

where fires raged and boomed

now an open pit

with a small dog’s heart

beating inside.

The poem initiates on an image of a dog alone in an open quarry. This image of vacancy prompts the speaker’s imaginative wandering—picturing the quarry in its former state of activity, teeming with people and life. She delivers us to the rich sensory detail of sweat and coffee—the epitome of coffee, with forty bubbles on its foam—only to snap us back to reality by returning to the smallness of the dog within the now-empty pit. But, unlike the way in which reality often enters into dreams, as an interrupting, deflating force, this reality does not constrain the fantasy that came before it. Rather, the two perspectives elaborate one another. In relation to the former life of this quarry, the dog’s small beating heart seems a diminishment, yet its persistence against the emptiness brings a new sense of hope it lacked in the first stanza.

There is so much to praise in these poems: the deft use of sound, the organic forms, the historical and mythological resonances. But what strikes me most is that these poems, like the best poems, are specific and singular, yet avoid becoming insular. And that is what distinguishes this work from dreams recollected over breakfast. These aren’t dreams that are told, they are dreams that are created for us to live in. This is a collection of universes, waiting to be inhabited.

Filitsa Sofianou-Mullen was born in Germany in 1962 and raised in Thessaloniki, Greece. She studied English Philology at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki and continued her graduate work at Kent State University in Ohio, USA. She has taught at Kent State, at the American College of Thessaloniki (ACT) and for the past ten years at the American University in Bulgaria (AUBG).Prophetikon, published by Scalino, is her first book of poetry. Others of her poems have been published in Voices from the Attic (the Creative Society series at ACT, which she co-edited for three years), in Fly in the Head (AUBG’s creative writing magazine), and various online and print series. She writes in Greek and English.

Filitsa Sofianou-Mullen was born in Germany in 1962 and raised in Thessaloniki, Greece. She studied English Philology at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki and continued her graduate work at Kent State University in Ohio, USA. She has taught at Kent State, at the American College of Thessaloniki (ACT) and for the past ten years at the American University in Bulgaria (AUBG).Prophetikon, published by Scalino, is her first book of poetry. Others of her poems have been published in Voices from the Attic (the Creative Society series at ACT, which she co-edited for three years), in Fly in the Head (AUBG’s creative writing magazine), and various online and print series. She writes in Greek and English.